Student journalists fighting school AI surveillance: 'Adults aren’t scary'

Ex-Kansas high school editors reflect on their fight against Gaggle, what they learned about press freedom

Last year, high school journalists in Kansas discovered their district’s new surveillance program was doing more than addressing a growing mental health crisis — it was violating their privacy, free speech and press rights.

They gathered evidence, raised concerns with administrators and faced obstacles and pushback. And they won.

Student journalists were ultimately removed from the surveillance program.

“It really showed us that adults aren’t scary,” said Morgan Salisbury, a former co-editor-in-chief of The Budget. “Oftentimes, you might know more about an issue that they do,”

Almost a year after their fight against the surveillance program, former staffers of The Budget at Lawrence High School, now college students, look back on why they took a stand, the obstacles they faced and the lessons they carried forward.

Their reflections were part of a discussion hosted last week by the Student Press Law Center for Student Press Freedom Day.

The surveillance tool

At the center of their fight was Gaggle, a program that monitors data within the district’s Google Workspace, giving administrators access to all school-provided Google accounts.

Implemented in November 2023 to prevent suicide and self-harm, the district said the tool helped comply with the Children’s Internet Protection Act, The Budget reported at the time.

Despite Kansas’ student press protection and shield laws, Gaggle also scanned student journalists’ work.

Former co-editor-in-chief Jack Tell said this gave school administrators access to confidential quotes and story drafts before publication.

“When we were writing about sensitive topics, we did not want school administrators to have access to those prematurely,” Tell said.

For example, in 2018, The Budget reported on teachers’ concerns that the district wasn’t notifying them about students who might pose a threat. The story touched on sensitive topics like sexual assault and violence.

Natasha Torkzaban, another former co-editor-in-chief, said the story, which was built on anonymous interviews with teachers, would have been flagged by Gaggle.

“If we wrote that story today, it’s very possible that the district administration could be legally required to view our notes and anonymous interviews, which would both compromise our integrity as journalists,” she said.

They also said monitoring students in public schools is “constitutionally tricky,” given the Fourth Amendment, which protects against unreasonable searches and seizures.

How it started

After the local school board approved Gaggle, the three student journalists began digging into different aspects of the program.

Torkzaban examined its $162,000 price tag amid a district deficit. Salisbury looked into the technology. Tell focused on its impact on students.

“We all came with different concerns,” Torkzaban said. “I think coming together and talking about that was so important during that time.”

Their advocacy gained widespread support. At least 320 students and teachers wore black armbands while the journalists met with administrators. They built momentum by presenting their case in classrooms and posting on social media.

“We talked to everyone — honestly, like everyone in our community,” Torkzaban said.

At first, Salisbury said, it was unclear what Gaggle was scanning. Then, an entire art class was called to the principal’s office after the software flagged their uploaded artwork.

He said that was when they learned that Gaggle scanned their work.

‘Sometimes, they just don’t know’

Given the school board’s unanimous approval, the student journalists assumed officials understood the program. But when they asked administrators how Gaggle worked, no one could explain.

“There was a point during the school year that I can confidently say between us, we were probably the most educated on how Gaggle worked,” she said. “And that’s something that’s very bizarre to me.”

Without clear answers, they ran their own tests — typing potentially flagged words into their Google accounts and watching to see if Gaggle detected them. It did.

Tell said he learned that if an email contained a flagged word, it wouldn’t be delivered to the recipient. He said he could imagine a scenario where a student in crisis reached out to a trusted teacher late at night, only for that email to never get delivered.

That realization drove them to keep going.

“It’s a reality that sometimes people who implement things don’t actually know how it works,” Torkzaban said. “But it was a huge, huge factor that motivated us to keep going.”

Jonathan Gaston-Falk, a staff attorney with the Student Press Law Center, said the students faced an uphill battle and pressure — as administrators had already committed tens of thousands of dollars to a multi-year contract.

Facing pushback

While the student journalists said the district was generally supportive of student advocacy and is press-friendly, tensions rose when they were in a meeting that included an attorney from the Kansas Association of School Boards, who told them he didn’t believe their arguments had merit.

Torkzaban said they kept making legal arguments, telling them they were wrong. She said their request to have an SPLC lawyer present was denied.

“We went into the meeting with these people who had their doctors, had their Ph.D.s, were professionals in this field and we were 17-18 years old at the time,” Torkzaban said. “All of this felt like a huge intimidation tactic for us.”

It was the meeting that “rocked” them, as Salisbury put it.

He said the officials were “largely bluffing” to try to “get us to go back to the classroom and settle down.”

But Tell said they remained confident throughout the process that something was wrong and their questions deserved answers. The pushback was expected, however.

“If you even start to question authority or question school administrators that your rights are being violated, they’re not going to respond to you ‘Oh, OK, we’ll stop that,’” Tell said. “You’re going to receive enormous amounts of pushback, no matter where you go.”

He emphasized people can violate your rights politely or aggressively, but a violation is still a violation. Pushback is inevitable, but if you’re defending yourself, it’s a sign you're on the right path, he said.

💬 I want to hear from you! Is your publication doing something cool that you’d like to share? Email me at nutgrafnews@gmail.com.

Story Spotlight:

📰 A Hawaiʻi Public Radio survey of 44 public high schools found that fewer than half still have a student newspaper journalism program while the student-run newspapers still alive are struggling to hang on. And that underscores a stark future for the state’s journalism industry.

💰 Fewer local businesses are buying ads with student newspapers, forcing the publications to rely more heavily on financial support from the institutions they cover, raising concerns about independence, GBH News reports.

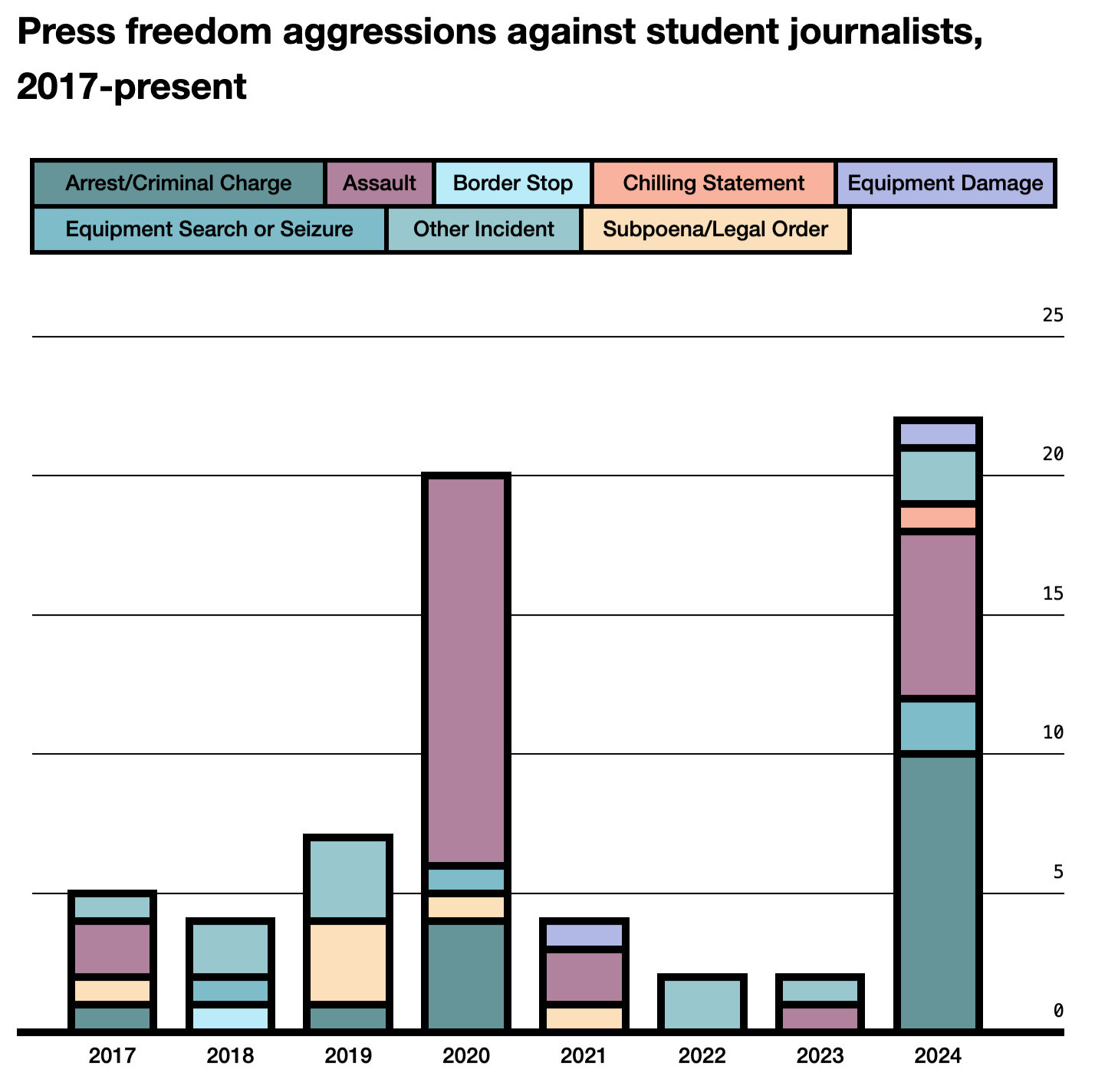

👀 U.S. Press Freedom Tracker looked back at press freedom aggressions against student journalists since its inception in 2017, with a particular focus on 2024. Last year, 19 incidents involving student journalists were documented, its highest annual tally to date.

Featured Opportunities:

n+1 is seeking a part-time editorial fellow to begin working in its Brooklyn office in March.

The Rochester Beacon is accepting applications for its summer internship program, The Oasis Project.

Press Pass NYC is hosting a free webinar for student journalists on how to cover immigration for your school newspaper March 4.

High school students may nominate themselves for JEA’s Student Journalist Impact Award before March 15.

Apply for scholarships from the National Press Club before March 16.

Apply for The Nation’s Fellowship for the Future of Journalism for high school students before March 17.

Slate is looking for a summer editorial intern for its Advice section. Deadline’s March 20.

The SPJ’s chapter in Washington is hosting a webinar on writing compelling fact-based stories March 24.